|

(Note: in

this article I use the term "wind rotor" meaning horizontal axis wind

turbine - not to be confused with the Flettner Rotor We have all seen things blown by the wind. Light objects can be blown along by the wind and travel in the same direction as the wind. But how can an object be blown by the wind in the opposite direction to the wind? Blown upwind? Does this seem impossible? Sailors know that

their boats can be blown along when the wind is coming from the side or

from behind. It IS possible because we can gain energy from the difference in velocities between two interfaces - the air and the water (or the air and the land).

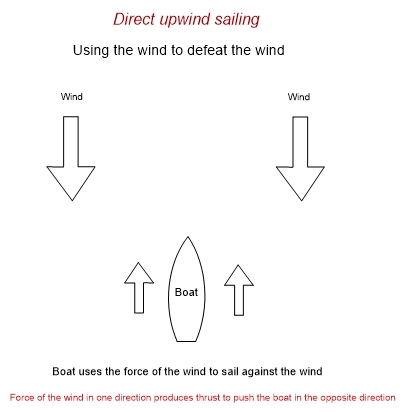

Force of the wind in one direction produces thrust to push the boat in the opposite direction The idea that a windmill mounted on a boat would give that boat the ability to travel directly into the wind is an old idea often suggested but not often successfully realised. For several years I did research to see the best way it could be done. Not having access to a wind tunnel my research had to use the real wind or sometimes just an electric fan. I don't believe wind tunnel air is exactly the same as the natural wind, which is full of gusts and eddies. Wind tunnels are very appropriate for testing aircraft or anything which travels through the air but perhaps testing something where the wind moves past, is not so suitable. So maybe my tests were more valid. Interest in wind assistance for shipping has been revived because of the mandatory regulations which are coming into force from the IMO (International Marine Organization) - an agency of the UN. These regulations are to be brought into force due to concerns about climate change and the fact that shipping is one of the greatest producers of pollution and carbon worldwide. Many companies are working now on systems for wind assistance to ships. A list with information on these can be found on the International Windship Association website. Some companies have developed their systems as far as producing prototypes but others are just pipedreams which have not been fully investigated or built. One notable exception are the Flettner rotors sold by Norsepower. These have been fitted to many different ships including a cruise ship "Viking Grace". Several systems are proposed to add wind-assist to ships. these include, Flettner Rotors, Savonious Rotors, Wingsails and kites. These systems get their thrust from wind coming from either side of the ship. They do not offer any power when the wind comes directly against the direction of the ship. Only one system offers the prospect of wind-assist from direct headwinds: Wind Turbines connected to an underwater propeller or fed into the main power shaft of the ship. These need not produce enough thrust to completely overpower the effect of the headwind, but just mounting a correctly adjusted wind turbine would assist the ship by providing more thrust than the drag it creates. My research showed that the type of wind-turbine best for allowing the greatest thrust from a headwind is very different from the type of wind turbine you might see on land for producing electricity, or even those mounted on yachts for producing electrical power. It is different. I found that the optimal design needs to allow lift to be obtained from the blades without the lift vector being inclined at such an angle that holds the craft back from penetrating the wind. On a fixed-base wind turbine this retarding lift does not matter because the unit is directly mounted on the ground which cannot move, but in the case of a turbine mounted on a ship which can be pushed downwind the situation is different and the unfavourable lift component needs to be minimised. This leads to rotor blades which revolve much slower than the fixed based land type.

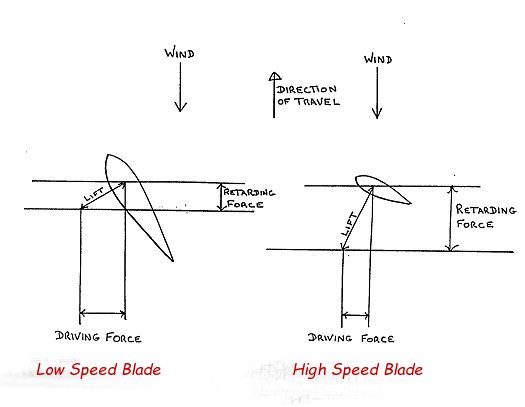

In the above diagram

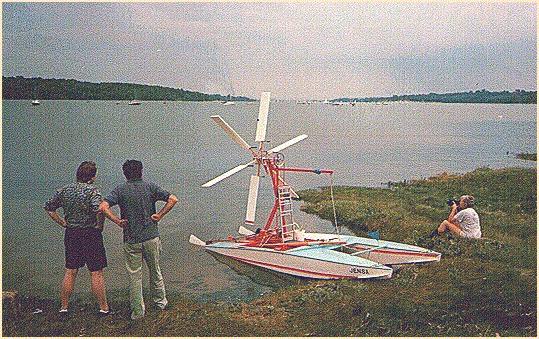

- 2 types of rotor blades are compared. I found that the most effective kind of wind turbine was a slow speed high torque design with the pitch of the blades set at no more than 45 degrees to the wind when stationary. With this 45 degree wind blade angle it means that the average of the blades rotation velocity does not exceed the speed of the wind. For example: in a 10 knot wind the speed of the turbine blades through the air would be 10 knots also. This would be a tip speed ratio of 1 - very low compared to the normal wind turbine tip speed ratios which are between 6 and 10. This slow rotation speed has many advantages. The operation of the turbine is safer and gentler than the usual type of wind turbine which has frightening blade speeds sometimes approaching the speed of sound at the tips. The blades on my own design do not need to be strong and heavy. In fact the wind blades on the 12 foot catamaran which I was using for testing "Jensa" were based on model aircraft wings and were open frame made of balsawood and were strong enough and never suffered any failure. The pitch of the blades was controllable from zero degrees to the 45 degree angle with a similar mechanism to a helicopter rotorhead. This can be seen in the video.

Because of the slow rotation, more wind blades are needed to cover the swept area of the rotor disk.. I usually made rotors with six or eight blades. The optimal design of wind turbine to give best thrust directly into the wind is so different than usual that I gave it the name "Rotary Sail". Why this name? Because each blade could be compared to a sail of a boat but rotating instead of being fixed to the boat and operating in similar airspeeds. The "Rotary Sail" idea was specifically designed to be used with wind directly ahead or direction about 45 degrees either side, it would not be optimal with full sidewinds because the gear ratio to the propeller would have to be changed and the rate of rotation increased which would lead to other modifications being required to the rotor blades. It would be ideal if another form of wind drive could be added such as a self-trimming wingsail. This would lead to a hybrid type of boat with both rotary sail and wingsail. Some of the testing I did was to see how SMALL a rotary sail could be and still be able to push a boat into the wind. For ease of use it would be desirable if the circumference of the rotary sail did not exceed the beam of the ship so that docking next to other ships or a dock would not lead to interference with the blades. Testing on models I found it was possible to have an effective rotary sail that was much smaller than the beam of the boat it was powering, and yet was still be able to drive the boat to windward.

Even with a wind rotor as small as this - it still worked! This is in contrast to some other builders who have mounted enormous unwieldy wind turbines on boats in the hope of catching as much wind as possible leading to impractical designs. I have assembled another page which shows evidence of direct into wind sailing from several researchers as well as myself. This page also gives plans of simple models that can be built to demonstrate the theory and possibility. I encourage anyone to build themselves one of these simple models if only to satisfy their curiosity as to whether it works! http://www.windthrusters.com/proof.html Ducted Rotor Further model tests were made using a wind-rotor with a circular shroud around the tips of the blades. |